OTA was first used by NASA, then by DOD to support funding for research and technology prototypes. OTA includes mechanisms for legally binding funding agreements with the government that are much more flexible than a standard federal contract, grant, or cooperative agreement. Instead, by March 2021, according to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), $12.5 billion was obligated by the Departments of Defense (DOD), Health and Human Services (HHS), and Homeland Security through flexible contracting mechanisms known as Other Transaction Authority (OTA). Spending $18 billion dollars in less than a year meant that the normal guardrails for funding transparency, including congressional oversight of appropriations and contract reporting mechanisms, were not in place. Whether it’s used in public health emergencies, climate threats, or other disruptions, how this model handles funding accountability and scientific expertise warrants more attention than it has received from policymakers. In less than a year, its financial cost was $18 billion dollars-on par with the Manhattan Project, which developed the atomic bomb at a cost of $23 billion (adjusting for inflation) over five years.

OWS was an exceptionally large expenditure. The key to gleaning these various lessons lies with better understanding how OWS functioned. Likewise, more nimble, expeditious mechanisms for scientific consensus could help the government function more efficiently overall. But the lessons could also be instructive, because more flexible spending mechanisms that can be deployed quickly in either crisis or normal times are critical to ensuring appropriate use of taxpayers’ funds. It clearly contains cautionary lessons: if OWS-type programs become a norm for government-either because they are perceived as an effective way to get results in a crisis or because the government finds itself responding to crisis after crisis-over time important attributes of transparency and deliberation in government may be deemed disposable. OWS could become the template for rapid government response to future crises. The rapid tests, monoclonal therapies, and mRNA vaccines that companies have developed or commercialized have saved lives, prevented suffering, and reduced further economic and other damage from the virus. The government needed to quickly develop novel modes of detection, treatment, and prevention in response to the public health emergency caused by SARS-CoV-2. The justification for suspending these guardrails was speed.

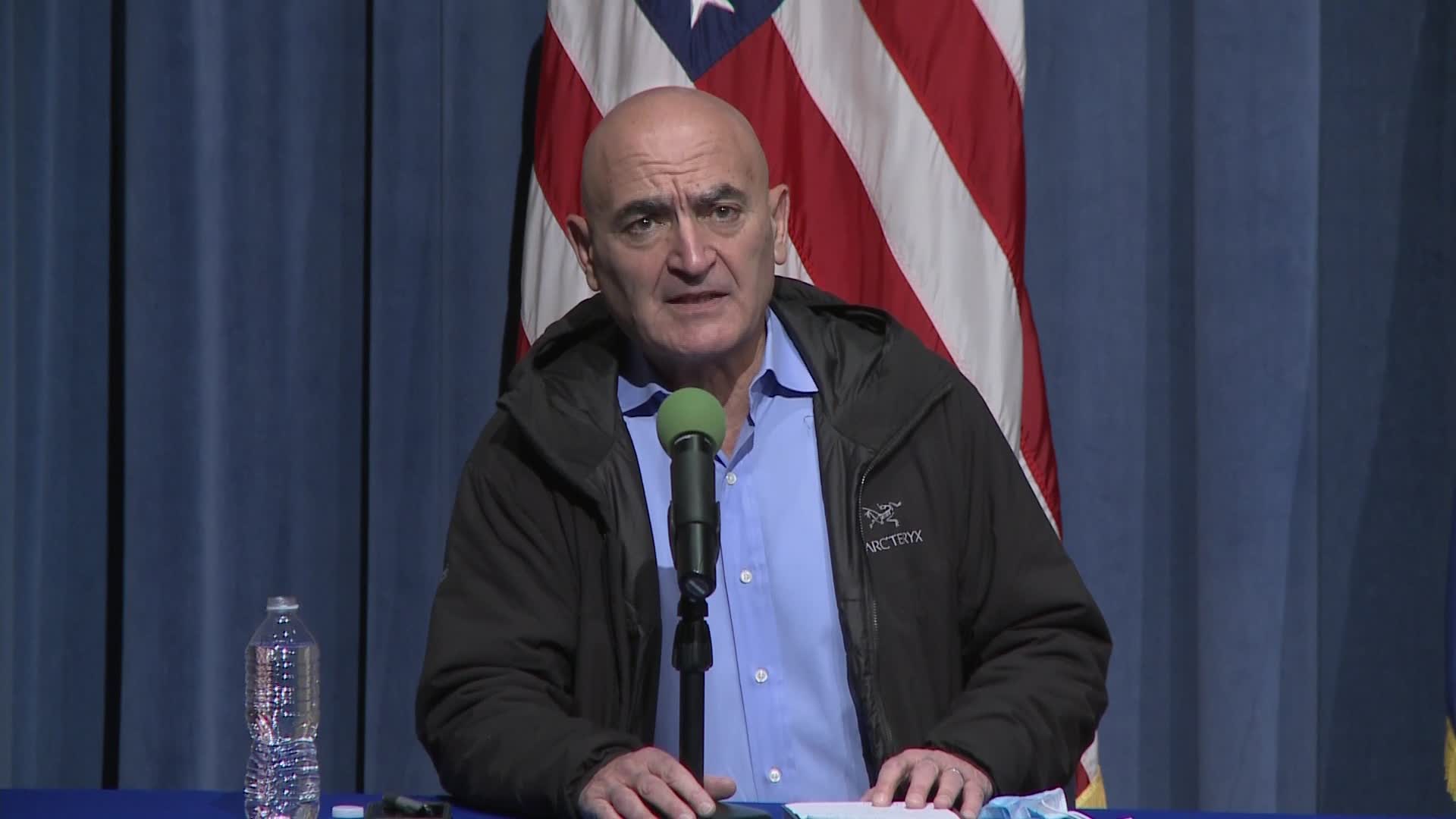

And although OWS accessed federal biomedical and preparedness expertise, it did so in ways that deviated from existing policy processes of scientific consensus authorized via advisory committees, systematic merit review, and other established practices. For instance, accelerated contracting processes replaced the usual federal contracting procedures. Making such rapid progress on the COVID-19 vaccine during a public health crisis required deviation from the federal government’s usual modes of operation: in particular, temporarily suspending or ignoring some of the usual administrative and scientific guardrails. Since the authorization, OWS has been viewed as a stunning success both inside and outside government. The vaccine development effort, called Operation Warp Speed (OWS), was co-led by Moncef Slaoui, former head of vaccines at GlaxoSmithKline, and Gustave Perna, a retired four-star general. Obtaining an effective vaccine less than a year after the COVID-19 pandemic began was an unprecedented achievement. On December 11, 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorized the first COVID-19 vaccine dose for people aged 16 and older.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)